idb-transaction-commit

IDB Transaction Explicit Commit Explained

Documentation & FAQ of the IndexedDB transaction explicit commit() API. Please file an issue @ https://github.com/w3c/IndexedDB/issues if you have any feedback :)

Last updated date: 10/10/2018

Table of Contents

- What’s all this then?

- Getting started and example code

- Key scenarios

- Detailed design discussion

- Spec changes

- Future features

What’s all this then?

IndexedDB’ transaction.commit() functionality will provide an explicit API for requesting that an IndexedDB transaction be committed.

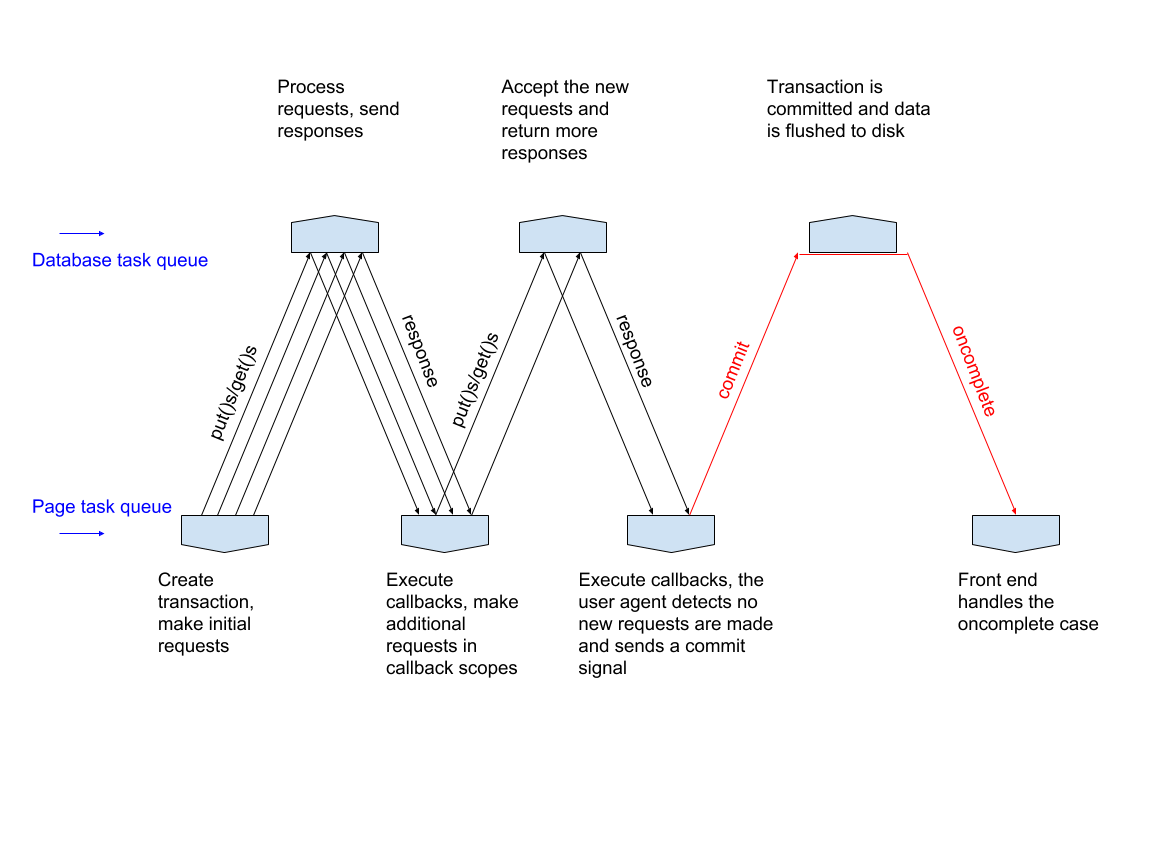

At present an IndexedDB transaction is autocommitted when the user agent determines that it is no longer possible to for the transaction to transition from an inactive state to an active state. Currently, a transaction is only active in the scope in which it is created as well as the scopes of any callbacks on requests made on the transaction. Thus, as long as callbacks from previous transaction requests themselves make new requests (for example, in the event that the results of a previous ‘get’ request are used to construct a secondary ‘get’ or ‘put’ request), the lifetime of the transaction will be extended and the transaction will not be committed. If all associated callbacks have resolved with no open requests on the transaction, then the user agent will detect this situation to mean that the transaction can no longer transition to an active state and thus it should be autocommitted (note that the process of committing here means writing IndexedDB changes to disk on the user’s machine). The current autocommit behaviour can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: An example control flow illustrating the transaction autocommit functionality.

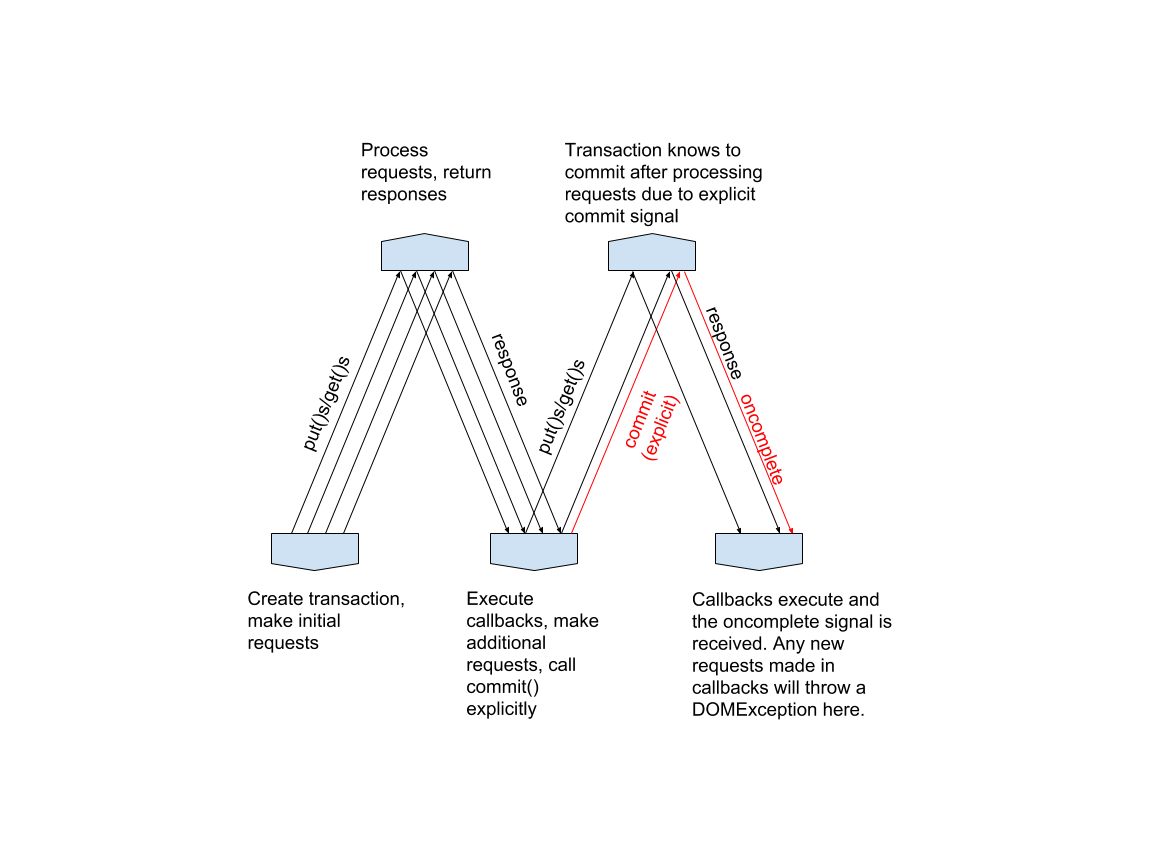

With the addition of the explicit commit() call to the IDBTransaction API, the strict requirement for the user agent alone to determine programmatically when a transaction is ready to be committed is removed. When the explicit commit() call is invoked on an active transaction, the transaction will be forced into the ‘committing’ state, and thus no new requests will be permitted to be made on it (even in any callbacks belonging to previous requests). Attempts at making new requests on the transaction after commit() is called will throw a DOMException. We see the difference between the current autocommiting implementation and the new explicit commit() call in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: How the previous control flow differs in the case of explicit commit().

Goals

The primary benefit of this change is increasing the throughput of writing data to disk.

Under the previous architecture, before a transaction could be fully committed and data flushed to disk, it was necessary for script to verify that no request callbacks themselves made new requests on the transaction. This meant that flushing data to disk required waiting for all pending callbacks to resolve completely.

IndexedDB’s explicit commit() call will allow developers the flexibility to announce the fact that they do not intend to make any new requests on a transaction object. As a result, the task of committing data to disk does not have to wait until a signal from the front end declares that all callbacks associated with the transaction have resolved; it only has to wait until all transaction requests have been processed completely by the database task queue. The fact that this final signal roundtrip between the database task queue and the page task queue is no longer necessary is evidenced by its lack in Figure 2 relative to Figure 1.

Increased throughput of writing data to disk for IndexedDB is obviously useful for performance cases, such as when large amounts of data are being written to disk (e.g. the initial population of a database), but it is also very useful for ensuring data integrity in cases when data must be written under some enforced time constraint (e.g. the situation described below in the section Page Lifcycle).

Non-goals

The explicit commit() function detailed in this document will NOT be replacing indexedDB’s autocommit functionality. This means that there is still no standard way to hold a transaction open at the complete discretion of the developer. Particularly, there is still no standard way of having a transaction depend on the result of async work. This is because a transaction is not blocked from committing because some work will be done on it in the future (e.g. after async work finally returns with some value that would be used to construct a query on a transaction), but because work is currently being done on it.

Getting started and example code

Using the IDBTransaction.commit() API call will be simple and intuitive and introduce very little additional code relative to what developers are already accustomed to writing. Developers will simply call commit() on any transaction that they know they are finished requesting and are ready to commit to the database.

// We go through a simple example in which a transaction is made

// that puts some data into an object store, and then commits it.

let data = get_some_data(); // helper function elsewhere defined

let db;

// Connect to the database

let openRequest = indexedDB.open(['myDatabase']);

openRequest.onsuccess = function(event) {

db = openRequest.result;

let txn = db.transaction(['myDatabase'], 'readwrite');

txn.onsuccess = function(event) {

console.log("Successfully wrote data.");

}

txn.onerror = function(event) {

console.log("Unsuccessfully wrote data.");

}

let objectStore = txn.objectStore('myObjectStore');

objectStore.put(data.key, data.value);

// Here we call the explicit commit.

txn.commit();

};

Key scenarios

Scenario 1: Populating a database

Oftentimes a user may desire to populate a large amount of data into a database without any intention of making any secondary requests beyond this large ‘put’ operation. In this event, to ensure populating occurs as fast as possible, the developer can call commit() after issuing all their ‘puts’.

// Here we collect a bunch of data to populate a database,

// using multiple transactions. Because commit() will speed up the

// flushing of each individual transaction, throughput increases

// dramatically.

let data_chunks = get_data_to_populate(); // helper function elsewhere defined

let db;

// Connect to the database

let openRequest = indexedDB.open(['myDatabase']);

openRequest.onsuccess = function(event) {

db = openRequest.result;

// Make all the transactions for the different data chunks

// and commit them.

data_chunks.forEach(async function(chunk) {

let txn = db.transaction(['myDatabase'], 'readwrite');

txn.onsuccess = function(event) {

console.log("Successfully wrote chunk: " + chunk.num);

}

txn.onerror = function(event) {

console.log("Unsuccessfully wrote chunk: " + chunk.num);

}

let objectStore = txn.objectStore('myDatabase');

chunk.data.forEach(function(datum) {

objectStore.put(datum.key, datum.value);

});

// Here we call the explicit commit.

txn.commit();

});

};

Scenario 2: Page Lifecycle

The Page Lifecycle API is an API heavily involved in alleviating power and memory tolls on users running many web applications at once. Central to this task is efficiently tracking and managing pages as they transition in and out of active and inactive states.

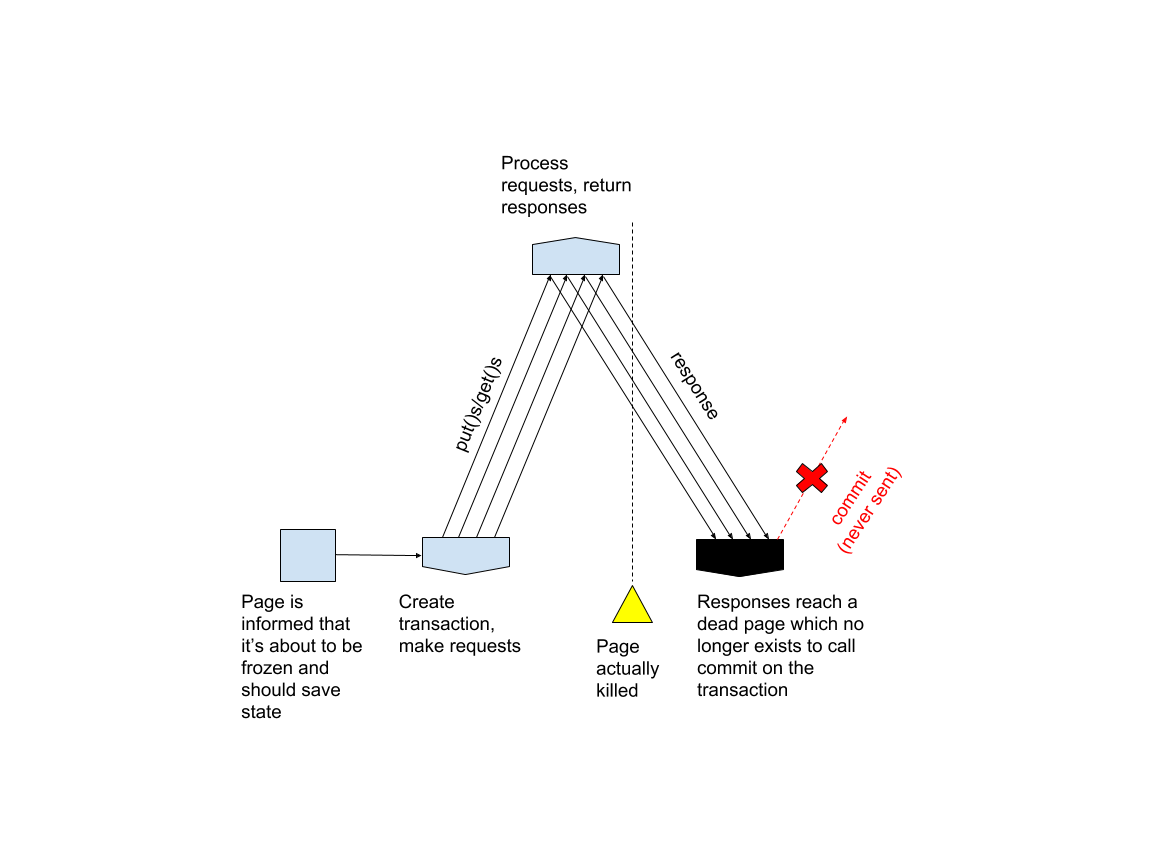

The process of ‘freezing’ a tab involves recognizing when a tab has been inactive for a long period of time, marking it for ‘freezing’ (letting it know that the browser is getting ready to kill its process to save on memory), and then subsequently killing it. When the tab is informed that it is going to be killed, it has a limited window of time to save its state to disk so that the website can pick up where it left off by re-loading this state if the user returns to the tab.

Currently ‘freezing’ and other such functionalities under the umbrella of the Page Lifecycle API cannot reliably use indexedDB to save state because there is a risk that the transaction responsible for saving state to disk will not commit before the page is killed. This unreliability arises because the page must be alive after the ‘put’ requests return to the front end in order to issue the commit signal after all callbacks have resolved. Instead there is a pattern of developers saving state to localStorage. This unreliability is illustrated below in Figure 3.

Figure 3: An example of the unreliability of using the current autocommitting implementation of indexedDB for saving page state during the freezing process.

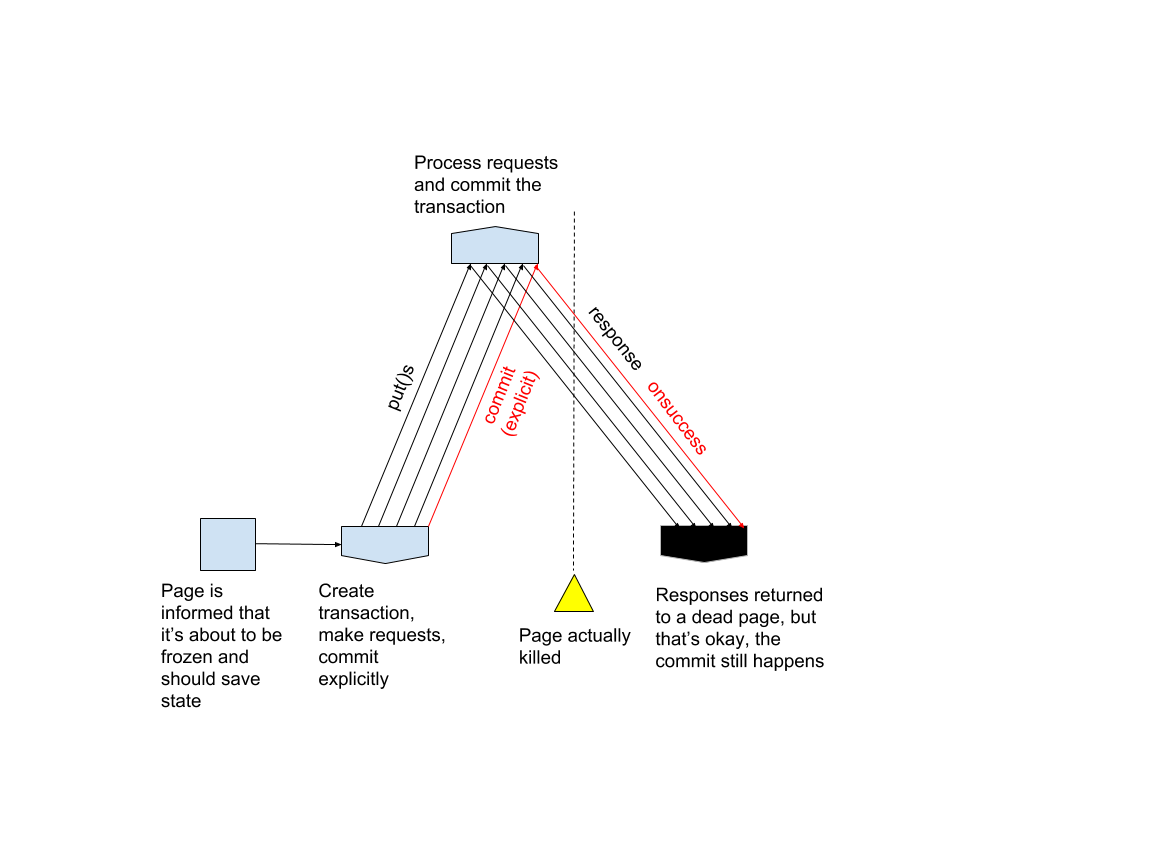

With the addition of commit() there is no longer a need for the page to still be alive after the ‘put’ requests are issued when saving state because, assuming commit() was appropriately called, the resolution of callbacks no longer mediates the flushing of data to disk, and instead it may be safely assumed that data can be saved with no performance implications. This fact is illustrated below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: An example of how the above situation is made more reliable with the addition of the explicit commit() API call.

By providing a reliable commit() option for indexedDB in the case of saving page state, developers will no longer have to rely on saving to localStorage, which will have a positive impact on website performance and input latency.

function onShutdownSignal(event) {

let pageState = getCurrentPageState(); // helper function elsewhere defined

// Make the transactions for saving state.

let txn = db.transaction(['pageStateDB'], 'readwrite'); // Assuming we already have an open db.

txn.onsuccess = function(event) {

console.log("Successfully wrote state.");

}

txn.onerror = function(event) {

console.log("Unsuccessfully wrote state.");

}

// Define the puts for the transaction

let objectStore = txn.objectStore('pageStateDB');

pageState.forEach(function(pieceOfState) {

objectStore.put(pieceOfState.key, pieceOfState.value);

});

// Here we call the explicit commit.

txn.commit();

}

Scenario 3: Best Practice

When a developer knows that they have made the last request on an open transaction, calling commit() is strictly beneficial to them. Their data will be written to disk faster and they will still receive responses from the final requests they have made against the transaction and so can still perform operations in script in reaction to the final requests being processed. Therefore whenever a developer is certain that a request is the final one they will make against a transaction, best practice will likely become that they call commit explicitly on the transaction.

let txn;

// Do most anything with the transaction here.

// When the transaction is ready, commit it explicitly.

txn.commit()

Scenario 4: Error Handling

It is possible for a call to commit() to throw an exception of type InvalidStateError. This occurs if commit is called on an inactive transaction (for example if commit is called on a transaction that is out of scope, has had abort() called on it, or has had commit() called on it). While for simple use cases it should be relatively easy to track the state of a transaction, when many dependent chains of requests are made with numerous request callbacks interacting with a single transaction it is even easier to lose track of the allowed transaction states. To avoid unexpected issues for complicated database interactions, it is a good idea to employ thorough error handling.

let txn;

// Make a lot of complicated and nested requests on the transaction here.

// Eg:

// let getReq1 = txn.objectStore(['store']).get('key1');

// getReq1.onsuccess = () => {

// let putReq1 = getReq1.transaction.objectStore(['store']).put({key:'keyP', value:'value'});

// putReq1.onsuccess = () => { ... };

// };

// let getReq2 = ...

// getReq2.onerror = () => {

// getReq2.transaction.abort();

// };

// let getReq3 = ...

// ...

// ... and so on

// In the onsuccess callback of one of these requests we call commit, but

// because we're uncertain about how the other requests and their callbacks

// may have affected the state of the transaction by the time this callback

// runs, we safely wrap the commit call in a try-catch block.

let getReqN = txn.objectStore(['store']).get('keyN');

getReqN.onsuccess = () => {

try {

txn.commit()

} catch (err) {

if (err.name === 'InvalidStateError') {

// Handle the case that the transaction is inactive.

}

else {

// Something else bad happened here.

}

}

};

Detailed design discussion

IndexedDB initially shipped solely with an autocommit functionality. Developers did not have the control to declare themselves finished with a transaction that the new explicit commit() API call affords them. It is thus reasonable to ask why the initial ship of indexedDB did not include an explicit commit() call and whether adding one could cause potential issues. The short answer to the first question is ‘simplicity’ and the short answer to the second question is ‘not really’.

Why an explicit commit function was not initially shipped

The first iteration of the indexedDB spec shipped with autocommit-only functionality to encourage short-lived transactions and to prevent bugs involving leaving uncommited transactions hanging around blocking future transactions from being opened on a database. Developers of indexedDB were concerned about web developers forgetting to call commit on transactions or holding transactions open too long, thus hindering the experience of web users. Because adding the explicit commit() call will not also entail removing autocommit, the autocommit feature will still exist to prevent dangling transactions and to close transactions as soon as they are no longer requestable by script.

Potential developer confusion

The primary concern about adding commit() is developer confusion, specifically confusion regarding whether and when commit() should be called. Adding commit() to the API may obfuscate the fact that indexedDB still has an auto-commit functionality. Developers may incorrectly believe that they must call commit() on all transactions lest they leave them dangling in the database. While this is a rather benign misunderstanding as it encourages always calling commit() and thus always increasing the throughput of the final requests made on a database, it is not ideal for the behaviour of indexedDB to seem at all unintuitive or opaque.

Obviously even if calling commit() always becomes best practice, autocommit will not likely be removed.

Spec changes

See https://github.com/w3c/IndexedDB/pull/242

Potential future features

Resurfacing commit errors

In the future there may be additional support for resurfacing commit errors that may occur when a page has been shutdown in the middle of a transaction being committed and is thus not around to receive the errors from the database task queue. Such an implementation would involve saving any errors that occur during committing so that if the page is loaded again at another time it can be delivered the errors that occurred previously and handle them.

References & acknowledgements

Thanks to Josh Bell for doing the spec work and helping explain commit().

Thanks to Daniel Murphy for his explanations as well.

Thanks to Shubhie Panicker and Philip Walton for their explanation of how commit() helps the Lifecycle API.

Thanks to Andrew Sutherland, Ali Alabbas, and Nolan Lawson for their contributions.